|

Abstract

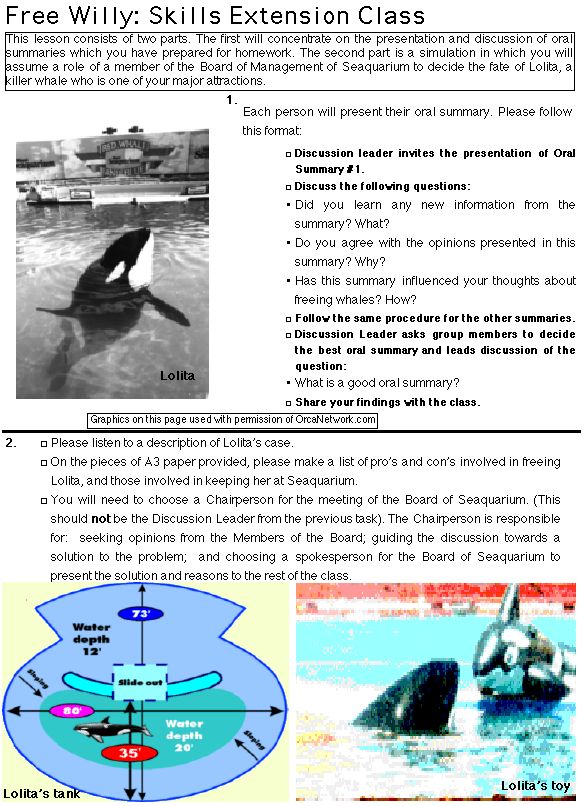

Integrating media to present a current news topic of a global or

environmental concern can be useful for increasing learners' critical

awareness of the complexity of views about a topic. As Jacobs (1995) states, "content-based approaches are not incompatible with attention to form. While content is key, form can be taught as it relates to purposes of language use ... [C]ontent-based instruction, particularly the use of socially oriented themes, represents an effort to link school with the world in which students live". This paper shows how one news story on an environmental theme was used as an umbrella to focus students on vocabulary, the news story and the issue

itself, discussions, learning about oral summaries (a genre), and

using the information from the oral summaries to become a participant

in a simulated meeting designed to encourage problem - solving and negotiation for conflict resolution.

The unit described is one developed in response to requests

through the end of first semester feedback form from four classes of third

year students at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies to focus on

current events and issues, debate, round table discussions and

negotiation. The students also indicated a wish to study idioms and

other "useful" language. As this was to be the initial unit for the second

semester, I wished to introduce oral summaries, since they would be

useful in the upcoming unit on gender selection and the debates

decided and researched by the students on "a current scientific concern",

which eventually included genetically manipulated foods, cloning, and euthanasia.

The unit described is one developed in response to requests

through the end of first semester feedback form from four classes of third

year students at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies to focus on

current events and issues, debate, round table discussions and

negotiation. The students also indicated a wish to study idioms and

other "useful" language. As this was to be the initial unit for the second

semester, I wished to introduce oral summaries, since they would be

useful in the upcoming unit on gender selection and the debates

decided and researched by the students on "a current scientific concern",

which eventually included genetically manipulated foods, cloning, and euthanasia.

Keywords: environmental education, critical pedagogy, EFL news clips.

|